Though each organism is inherently a time traveler, its genes a partial chronicle of its evolutionary history, we may be the sole species to be able to reflect on that deeper history. People with deep imaginations can visualize the ape in our behaviors, the prototypical vertebrate in our embryos, the symbiotic merger reflected in our mitochondria. Some can look at a hillside and envision it as a product of tectonic upheavals, erosional incisions and depositions, the lithification that turned sediment into rock that has weathered into a substrate supporting juniper, cactus, and spiny lizard. With some training, there is hope for those of us who don’t normally see so well. Our temporal blinders may be lifted, our spirits uplifted by the joys of discovery and insight. Informed imagination – that greatest of time machines – can take us further toward understanding the Sky Islands than mere physical descriptions ever will. Join me, then, for a little time travel, not to see it all (who has time?), but for a sample of how informed imagination works.

* * *

In the western part of the Sky Islands lie the Pajaritos, rolling hills of Madrean oak woodland that continue similar formations galloping northwest across the landscape from near Imuris in Sonora. The range lacks major peaks or well-maintained roads, so it is not on the minds of most people exploring southern Arizona, at least not for casual tourism. To a naturalist, however, a trip to Sycamore Canyon is an essential biodiversity pilgrimage. The canyon is noted for unusual birds, reptiles, amphibians, and plants and as a corridor through which drugs and illegal nonresidents traffic. My friend and student, Craig Childs, and I have come for the former, not the latter.

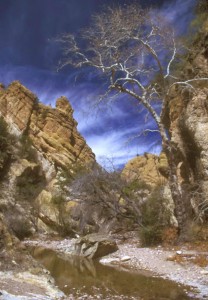

Sycamore Canyon is a biodiversity hotspot, an intersection zone. The narrowness of canyon walls, the presence of cool-air drainage, and the moderating effects of the water create a biogeographic inversion. Species of plants and animals typical of higher elevations occur at the lowest elevations anywhere within their ranges, often within a short distance of desert organisms you might find in the arid hills around Tucson.

Craig and I follow the stream into the Upper Box, what Rick Taylor calls a “tortuous stone vise.” We spider carefully across slick rock with deep pools of water below; this barrier discourages the faint and infirm from further exploration unless they are willing to get wet. We scramble up the rock face to the right, then continue climbing up a steep side drainage known as Arch Canyon. Craig, a skilled, practically fearless climber, ascends the cliffs with practiced ease. I grip faint projections and spindly plants for support as I labor up the near-vertical faces of rock down which water stains lead to gouged-out plunge pools or tinajas. I can imagine myself sliding or tumbling far down into a tinaja that would hold my crumpled form until the residue would be swept out by the force of a flash flood. Cheery thought. But if I get out of this alive, surely I will be one of a very few to have ascended this obscure and remote side canyon.

High in this narrow defile, we reach a deep but highly isolated pool. To our amazement, there are fish, Sonoran Chubs (Gila ditaenia), seemingly doing quite well in this tinaja. It seems impossible that they could have swum up here, even in the most extreme flood, for the high waterfalls surely must be impassable barriers. It’s also doubtful that a tornado or waterspout could have transported the fish here, even though fish have been noted falling from the sky in other parts of the country. Could a bird have lifted fish or eggs up here? Could people have done it? That seems very unlikely, for this is a hard place to reach, and little bitty chubs are not what fishermen would introduce anywhere, especially into a pool that must be isolated when the rest of the creek dries up. A puzzle to ponder.

Over a year later, that puzzle still on my mind, I asked W. L. Minckley, who knew fish distributions within the Sky Island area better than anyone, about this puzzle. I first asked if he or any other native fish expert might have moved the fish to this tinaja. No, he hadn’t had a thing to do with it. His guess was that the fish were there before the canyon was. What? Yes, if you go back a few million years, this canyon would not yet be eroded and sculpted into its present form. The tributary then would have had continuous connection; the canyon as we see it now did not yet exist. He’s seen this up near the Grand Canyon, too: an isolated fish population high in a side canyon up which no fish could possibly swim today. The carving action of the Colorado River there and Sycamore Creek here pulled a fast one on the fish living in those ponds.

The implications are staggering. If this scenarío is true, then the fish there today are descendants of thousands of generations of chubs for which that pool was their entire universe. The droughts and floods that must have occurred over those several million years never did completely dry or scour out the life of the pool. Genetic continuity of the fish is completely dependent on aquatic continuity. One demographic failure would have cut off the line, and today we would see a fishless pool and assume that it always had been that way.

Craig and I had looked at this isolated population and wondered how fish could have gotten up there. We were thinking in terms of dispersal. Minckley’s hindsight went a lot deeper. His reasoning didn’t limit itself to the major landscape changes that we know occurred throughout the Southwest in the late 1800’s. Nor did he focus on the events of the last 10,000-20,000 years, as many biogeographers do. Why get hung up on the late Pleistocene? Minckley saw that the evolution and distribution of fishes in the Southwest are part of a longer saga, perhaps mostly formed in the past 29,000,000 years since the North American Plate collided with the East Pacific Rise. Tectonic activity (mountain building, rifting, etc.) and subsequent erosion may have isolated once-connected populations or moved them around. What we currently perceive as barriers to dispersal may be immaterial to how fish got somewhere. Minckley told me: “Modern fishes are thus much older than conditions under which we find them today.”

Minckley and collaborators in 1986 gave another remarkable example of how geology may have shaped modern fish distributions. The Arroyo Chub, Gila orcutti, is found in the Los Angeles Basin today, but its nearest relatives appear to be the Sonoran Chub (G. ditaenia) and the Desert Chub (G. eremica), both in stream systems that drain into the Gulf of California in NW Sonora. That geographic gap might suggest pretty impressive dispersal, but the ancestor of these fish has been around for quite some time. If you go back 30 million years or so, the Gulf of California didn’t even exist. Things changed dramatically 29 million years ago. When the East Pacific Rise crashed into the North American Plate, the San Andreas Transform system developed, sending microplates, continental fragments, off to the northwest. The ancestors of Gila orcutti did not swim to southern California; they rode there! Other lines of evidence, genetic and geological, support the likelihood of this zoogeographic terrane track.

The take-home lesson of these discussions is that our typically short temporal imagination can inhibit our understanding. What we see today is not all there is to see. A thoughtful biogeographer, a creative soul with an informed imagination, is a far better time traveler than most of us. An ecologist may wonder if competition between two species might have limited the ranges of two similar species, but a different story may lie hidden in the stones or in mitochondrial DNA. The quest for understanding is simultaneously challenging and humbling; in fact, there will be some answers we’ll never know with certainty. At least we can enlarge the range and accuracy of the questions that we ask . . . and enjoy the mysteries that remain.

This article appeared in Restoring Connections of the Sky Island Alliance in 2004 and was reprinted in 2010. The Sky Island Alliance is a great group of folks working on conservation issues in the US-Mexico Borderlands. Please check them out and join in their efforts, if you can: http://www.skyislandalliance.org/.

My husband and I just hiked the upper portion of Sycamore Canyon and want to learn more about this amazing area. Your article was fascinating!

Thanks!

Thanks. It is indeed an impressive site.