In nature, every sound has meaning.

Stepping out of the house this morning to scatter a handful of bird seed for the local quail and other welcome guests, I heard an unexpected sound—a few series of sharp, somewhat hollow kowp calls that made my hair stand on end. A Yellow-billed Cuckoo! As our house sits atop a dry jumble of granite boulders, one of the last birds I expected to get on my yard list was the stream- and thicket-loving cuckoo, but there it was. Unmistakable if you know the sound. And the calls were coming from appropriate habitat, the green ribbon of cottonwood, willow, and ash trees that follows Granite Creek a hundred yards or so away.

A cuckoo at this elevation in central Arizona is an outstanding find. Adrenalin surging through my body, I had no need for coffee to wake me up. I grabbed binoculars and took off toward the creek, hoping against hope that I might find the bird. Cuckoos are notoriously difficult to see; they are shy skulkers, and they call irregularly. This was a needle-in-the haystack search, and I knew it. Though I was 100% positive that I had heard a cuckoo, would my reputation prove sufficient if I reported a bird heard a hundred yards or more away? For no more than a minute or two?

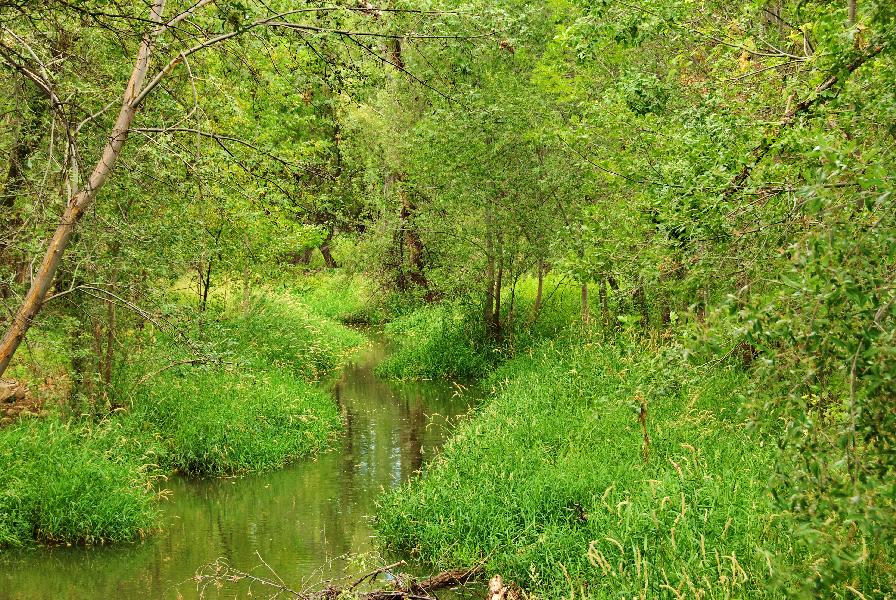

There was great diversity of bird sounds at the lush riparian area, but no cuckoo sounds. One thing about creeks like this one—they run in both directions, upstream and down, and if I guessed wrong, I might not hear the bird again. My hunter instincts were strong—it had to be downstream.

Ten minutes later, I rock-hopped the creek. Each time I stopped to listen, my senses were flooded with information, but that information did not include cuckoo. The crazy cackling of a Yellow-breasted Chat, the buzzing of two Bewick’s Wrens in bushes dangling from a granite cliff, the rapid twitters of White-throated Swifts slicing the air above , and the annoying chainsaw screams of cicadas caught my attention, as did the high whines of mosquitoes homing in on my bare legs, arms, and ears on this sultry morning.

Instinct time again. Do I work back and forth along this stretch of the stream, the area closest to where I heard the bird earlier, or do I take a chance and go further downstream, which would mean a detour well away from the creek to get there? Instinct spoke. I left the creek and walked up to busy Highway 89, where cars whizzed past me at 60 miles per hour as I threaded the road edge against a steep roadcut (really vertical rocks).

I approached the once-notorious Pinyon Pines biker bar, as incongruous as any structure might be next to a riparian area. Boarded up just during the past year, it sports a “For Lease” sign. Another historic Granite Dells cultural feature stands abandoned, as so many have over the years. Personally, I will welcome the quieter evenings along the creek without the blaring music and cycle revving that used to be common there.

I stood for ten minutes behind the bar on the edge of its gravel parking lot looking out over willows and walnuts under taller cottonwoods. Acorn Woodpeckers sallied out to catch insects, and some birds made frequent trips into the nest cavity in a towering snag. The woodpeckers tolerated the tiny goldfinches landing in the snag’s upstretched branches, but they made aggressive passes at three Bridled Titmice that foraged in dried bark not far from the nest site; the titmice ignored them. Brilliant Summer Tanagers, Blue Grosbeaks, and Hooded Orioles made appearances, and I certainly did not mind standing there, cuckoos or not. Finally wearying of waiting, I decided to head back out across the parking lot and follow the old road a bit farther, where I might find the Common Black-Hawks that nest there. It was getting quite hot now, and I had not grabbed a hat when I left quickly this morning. Nor had I had any breakfast. I was thinking that this might be a wild cuckoo chase, though one in which the birding was excellent.

Just then behind me, right where I had just stood, came loud clacking or knocking sounds, like the sounds you can make by dropping your chin and snapping your tongue hard against the floor of your mouth, only much louder. Though quite different from what I had heard this morning, this too was the sound of a cuckoo. I raced back across the lot and up to the overlook above the creek. I feared my haste might scare the bird if it saw me, but I could not hold back. I stopped at the edge, simply hoping to hear the sound again. Silence. But then the cuckoo flew from the dense Red Willows right toward me, landing at eye level just twenty feet away in the bare, silvery branches of a small dead cottonwood, where it began to strip fibers of dried bark that it most likely was using for nest-building.

What a gorgeous bird! A field guide says “clean white underparts,” but that evokes an image of new men’s underwear. No, the dazzling snow-white- alabaster breast, the corn-yellow curved bill, the hint of rich rufous in the primaries, and the striking white-and-black of the graduated tail feathers combined to make this a bird beyond words (though this is my feeble attempt to at least acknowledge the beauty).

After the bird flew off with its beak full of cottonwood fibers, I stood for a long while, almost dazed with my good fortune, grateful to my instincts. On my return walk, I repeatedly flushed a Common Black-Hawk (anything but common at this latitude), which flew low up the winding stream channel through a tunnel of greenery.

Five minutes or so from home, there they were again—the kowp calls that I had heard early this morning. This bird was high in a towering cottonwood; as I trained the glasses on it, it flew from one tall tree to another. I suspect this may be the bird I heard early, and it could well be different from the one building the nest some quarter- to half-mile downstream.

Cuckoos are rare in the West today, reflecting the enormous losses to the riparian areas once found there. When I see a cuckoo, I realize that this is the tropics come to me. The steamy heat of the summer monsoon season is what attracts them, a time of fat caterpillars and praying mantids and lush foliage along streams where nests can be built out of the sight of egg-hungry predators. As fall approaches, the cuckoos slip away back to their tropical haunts. These are snowbirds in reverse, catching Arizona at its hottest. They never experience real winter.

This is part of what it means to be a naturalist. Attentiveness to an unusual call, recognition, pursuit, confirmation. Hearing and seeing the cuckoo transported me straight to the tropics, or at least provoked my “informed imagination” to go there. It told me more about my home place, as well, showing how a multitude of avian threads tie the continent together. It confirmed my connection to all things wild and free. And yes, as some might remind me, through that connection, it proves that I am, indeed, a little bit cuckoo.

© Walt Anderson and Geolobo, 2011. Photos of Prescott Creeks

Pingback: Granite Dells & the Lakes | GEOLOBO